The rest of the boxes were clean and clinical, but this one was full of dust and glitter.

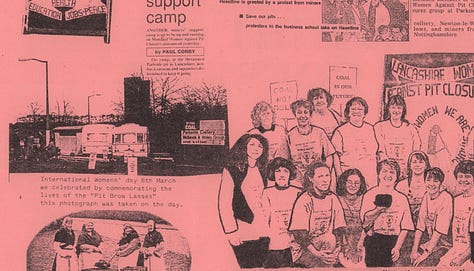

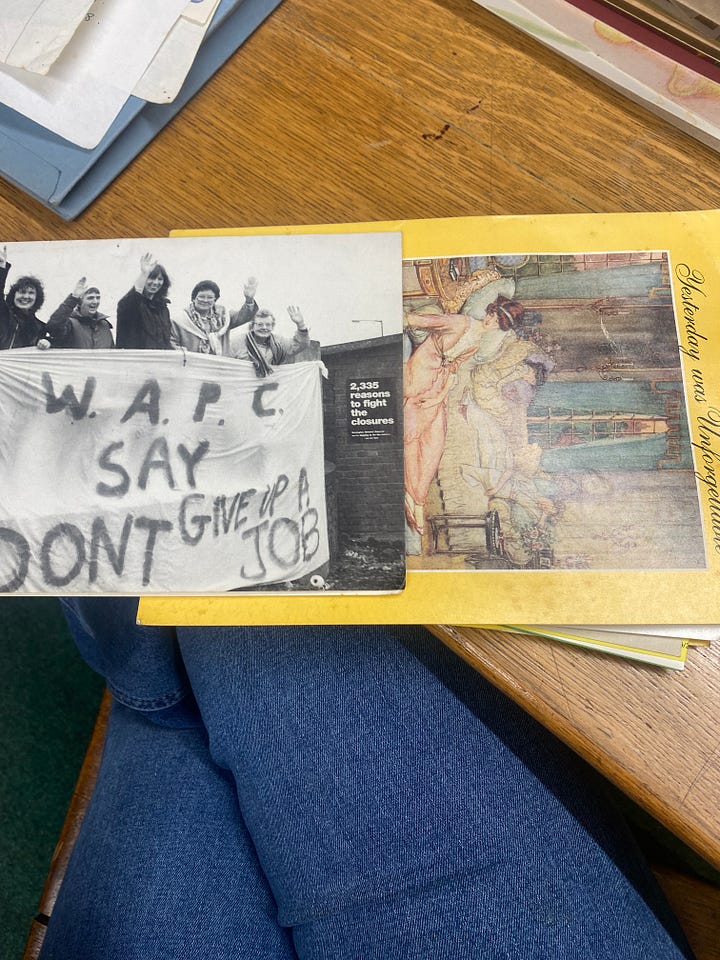

Last Tuesday, I spent the afternoon at the Working-Class Movement Library in Salford. I was there to look at material relating to the Lancashire branch of the Women Against Pit Closures movement, who in 1993 set up camp at Parkside Colliery in Newton-le-Willows, protesting the imminent closure of the last deep mine in the region. I was interested in the action at Parkside partly for a project I’m currently working on with the National Mining Museum and partly because the site of the camp is about twenty minutes drive from the town where I grew up.

For the past five years, I’ve mostly written about contemporary literature, and so have mostly avoided rites of passage in intimidatingly well-catalogued archival collections. The only proper archival work I’ve ever done was a term working on Angela Carter’s papers in the British Library, an experience which basically upended everything I thought I knew about Carter, and about archives, alike. If you’re looking for a sexy, funny, unruly collection of personal papers to get acquainted with, hers is the one for you. After that experience, I wrote an essay about the place of her erotic writings within the affectionately sterile climate of the BL’s Special Collections, and the strange bodily dynamics of archival work more generally, for a Dutch journal called FRAME. Several years later, I found myself in the WCML, similarly occupied by an intimacy with the materials I was handling, and feeling once again as though I wasn’t quite doing research properly. I hunted through folders looking for names and images I recognised, or for mentions of local landmarks. I felt like more of a curiously parasocial gossip than a researcher (perhaps no bad thing). I’m always looking, I think, for markers that the history I’m handling might in some way belong to me (it does not).

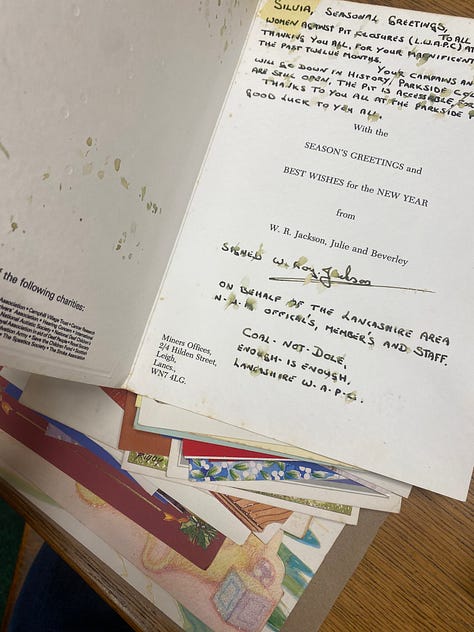

Most of the day was over when I hit upon a box that contained three folders worth of greetings cards. All of the material I’d seen that day had moved me in some way, but these folders were different. They made me want to cry and to laugh and to scream. I wished that I could put them in my bag and take them home and look at them over and over. I wished that I could relick their stamps, and share them with everyone I know. I wondered at first if I should try to write something longer form about them, or to pitch this piece elsewhere. I might yet, but what follows is an attempt to sketch out something of how I felt on Tuesday, as I stood on the platform at Salford Crescent, waiting for the train home, buzzy and impatient to write.

The greetings cards ranged over the full span of the period of the campaign, around twenty months in total. The folder that contained them bulged. Many of the cards themselves were stuck together, like pages in a family photo album that have to be creakily peeled under nervous surveillance. The WCML is a well organised, well catalogued institution, and most of the WAPC material had obviously been looked over regularly, but this box was clearly much less popular. Several of the documents in the collection mentioned the brasier, a mainstay of the pit camps, a reminder to KEEP THE FIRES BURNING, and a hearth around which the women would gather. Yet it was only in this box, presumably due to a lack of airing in other contexts, that you could still smell the smoke. The cards themselves were thick with dirt and dust, and it was only when I got to the end of the first pile that I realised I would need to clean my hands before continuing. They were now dirty and dusty, too.

As I realised how dirty these documents were, I couldn’t help but also think of Carolyn Steedman. (I am basically always thinking about Carolyn Steedman). In her book Dust, Steedman writes that that titular dust is the thing that matters most in the archive. Dust is the testament to “circularity, the impossibility of things disappearing, or going away, or being gone.” Dust is the reminder of the bodies that came before, and since, and of the impossibility of doing research without all of those bodies bursting, inelegantly, into the scene, coughing and spluttering all over your neat little desk. Such is the importance of all those dirty particles that for Steedman, the archive, and the dust scattered through it, might be best seen as one. At one point, Steedman quotes Jules Michelet: “I breathed in their dust.” And on Tuesday, a little overcaffeinated and pent-up from the train, that’s exactly what I did. A polaroid of the brasier was smudged with ash, quickly deposited onto my skin. These folders were not so much musty as oddly alive. If you can’t already tell by my predictably romantic prose, I think there’s something of a thrill to this, to the feeling of the traces of other bodies, close, in places you didn’t neccesarily expect them to be. It lends itself well to indulgent descriptions, but it’s also politically useful: it can move us, jolt us shakily into new consciousness, reminding us to adjust our eyes, and see ties that might have softened out of focus. As part of my research this month, I’ve been reading Lola Olufemi’s doctoral thesis. One of the things it tries to account for is how archival encounters such as these can work in affective, politically mobilising, ways, against the (felt) stasis of the present political moment. Notwithstanding that most people don’t have the time in their days to read PhD theses, Olufemi puts this much better than I can here. She stresses the “imaginative-revolutionary potential” of cultural objects in the archive, and their capacity to “reinvigorate the resistant desires necessary to build a liberatory structure of feeling." I was thinking of this idea through much of the day.

There’s something else too: an anxiety, an important hesitance. Feeling the dust and ash on my hands, I was acutely aware of the feeling of being too close to a false flame, by which I mean, aware of the pretence of that visceral connection, of the deceptive places that these apparently intimate materialities can lead us to. The women I was reading about in the archive, (women who manned the pit camps for 24 hours a day, and travelled across the country, sometimes across the world, to talk about their experiences and their struggles) are separate from me in ways that a fleck of dirt or a shared hometown can’t overcome. We’re separate in space and in time, and in the gulf between the experience of facing state violence on a protest camp, and of needing to clean your hands, the ever-diligent student, for fear of impolitely damaging historical evidence. The project I’m working on with NCME thinks about women’s engagements with coal mining across the twentieth century, and I wonder if there is something particularly acute about feeling that gulf when it comes to the culture and imagery of coal. It is a separation that feels particularly explicit, particularly easily visualised, that between the world above ground and the world below it, between those that kept their hands clean, and those that couldn’t. The whole point of this project is to challenge those binaries in relation to gender, but perhaps it is that stark context that made the sight of my own hand; darkened with dirt, and yet otherwise feminine, neat, adorned with relatively expensive jewellery, feel like a site of burning contradiction. I enjoyed the visual, all the same. Archives can be strange places. They can expose uncomfy feelings and weird desires.

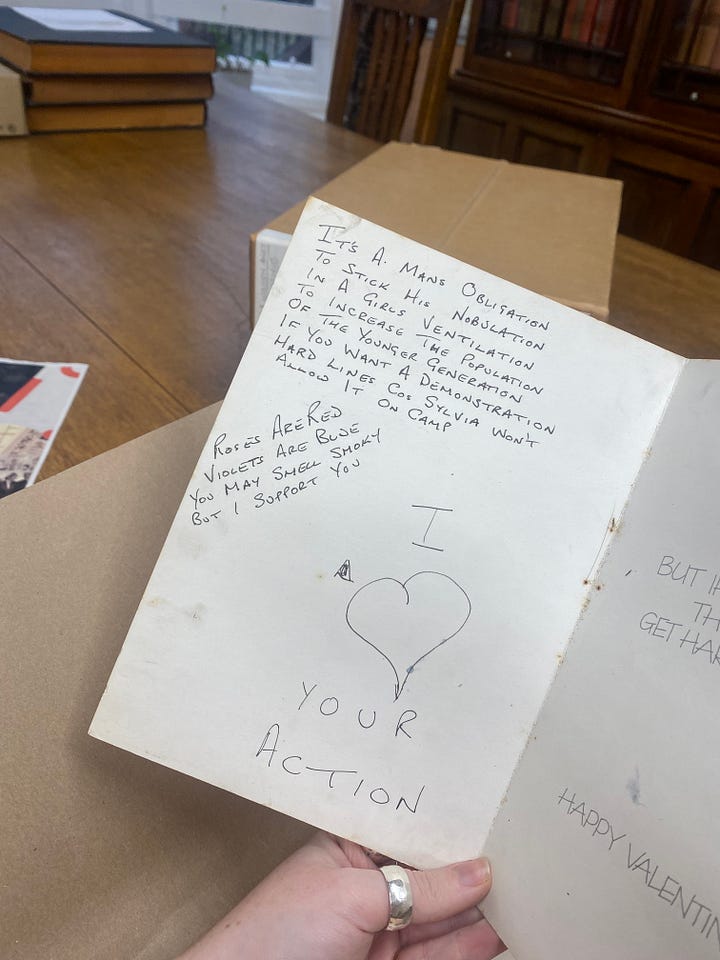

Back to the cards themselves, where the hands of others lead something of a way. They weren’t placed in any order, and so all the calendar came bundled together, life jumbled up, a dizzying path between cradle and grave. There were Christmas cards, of course, but also birthday cards, condolence cards, celebrations of birth, numbers of days at the camp marked, and perhaps my favourite of all, Valentines’ cards, too. I don’t think it is only because I wrote most of this post on Valentines Day that it was the latter that stuck out so. Instead, I think it’s that it was the Valentines’ cards that seemed so enjoyably incongruous with the setting, with the “proper” politics of working-class life. It was the Valentines’ cards that seemed most aesthetically striking within that context, and which seemed so tightly coded as feminine, the coding from which much of the apparent incongruity came from.

My favourite was a bright pink number with a lightly sexist line about “soft” versus “hard” gifts, very British, very Carry-On, made even more so by an innuendo-laden handwritten poem on the inner page. In it, any residual traces of the erotic are quickly punctured (if they weren’t already absent) by a final punchline: “Hard Lines Cos Sylvia Won’t Allow It On Camp.” Sylvia Pye lead the occupation of Parkside, and sadly died in 2018. Then a different tone: I HEART YOUR ACTION, which put me in mind of those often quite annoying graphics generated by left-wing institutions, that make romantic messages out of revolutionary figures, and are posted on Instagram in February, most often to sell products. Will You Seize the Means of Production With Me <3, etc. Only of course, this isn’t like that at all, it’s a genuine token of love and solidarity with little other motive, carved out in biro, full of laughs and smirks and smudged ink.

The fact that it is now here, gathering dust in a named and numbered box unsettles me, a little. All that flirtation and energy and relationality sealed up in cardboard made clinical. I suppose that’s partly why I wanted to share it, here. Who does this material exist for now? It’s absolutely right that it should be treated as historically precious, worthy of preservation, but that doesn’t totally negate the questions that arise from archives full of social history. Often despite their best efforts, those spaces most often largely inaccessible to the same communities that actually made that history, the same communities to whom these materials are surely worth the most.

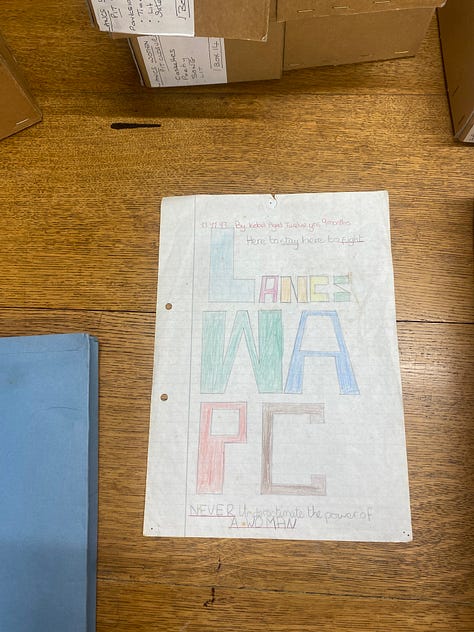

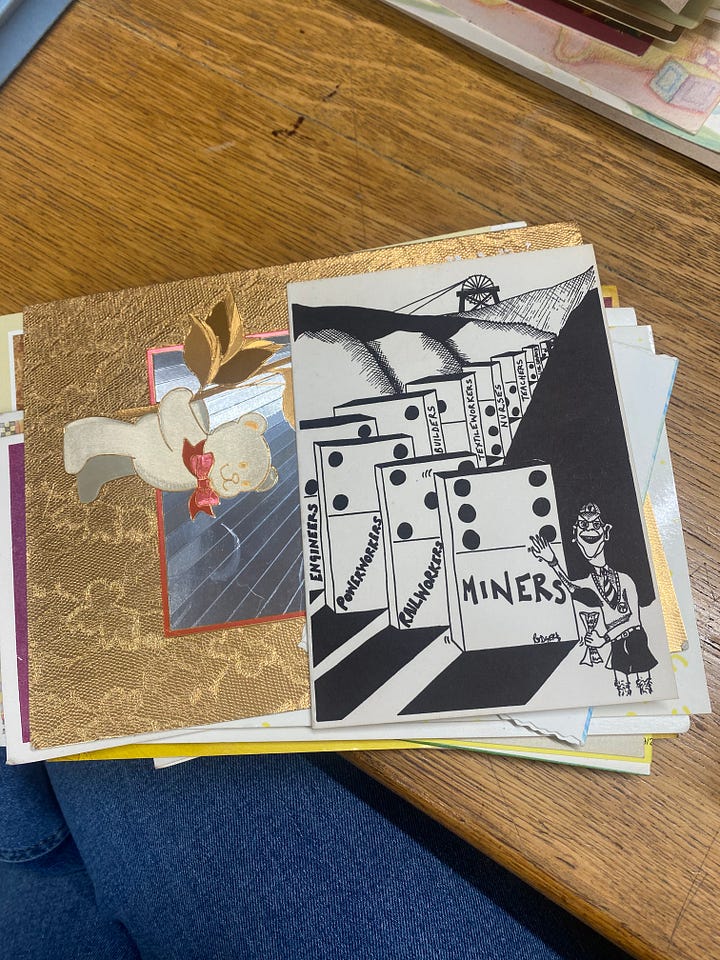

That question of access takes me onto another aspect of the greetings cards, which is the democratisation that they force. No card had been better preserved than others, seemingly none seemingly discarded for irrelevance, and no order to speak of, either. Instead, brightly coloured notes from primary school children were stuck up, stubbornly, against a note of support from Tony Benn. Any such democratisation has its limits - in this case, perhaps, the difference in the materiality of the cards themselves (punctured exercise book lines against a confidently middle-class art gallery postcard), but the fact remains that the two objects are presented as expressions of solidarity, one and the same.

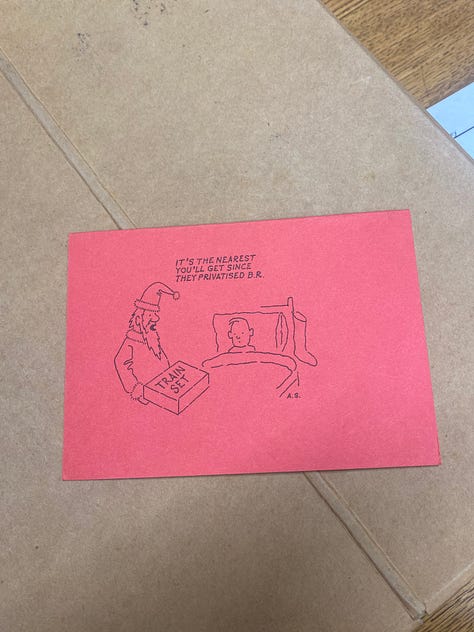

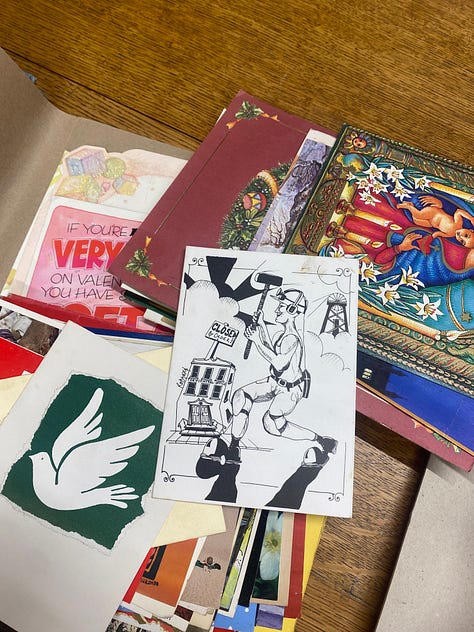

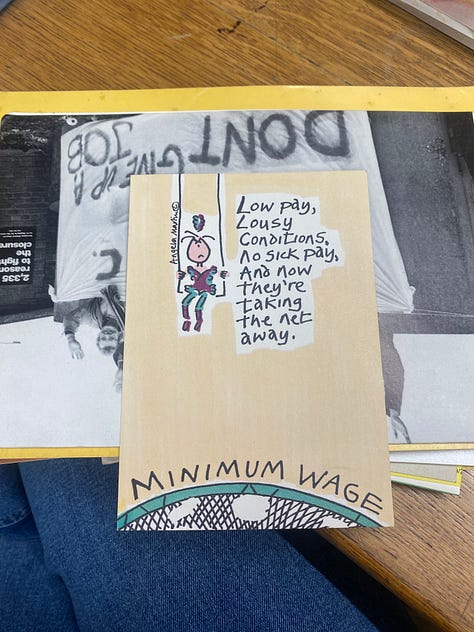

If anything, traditional hierarchies are reversed: the coloured pencil drawing, or the poetic Clintons’ classics, were to my eyes at least, much more affective than Benn’s floral muted, contribution. Perhaps that’s because I’m instinctively drawn to more gauche aesthetics, the poppier the better. Struck by the visual gift of these cards, I wondered how to find a way of understanding their aesthetic value, and how those aesthetics seem to chime or clash with the “official” politics at hand. Part of what made the box so much fun to work through was the endless aesthetic diversity of the cards themselves. Some of them were more obviously, or at least more explicitly, politically interesting, full of original illustrations and cartoons, some fascinatingly international, too.

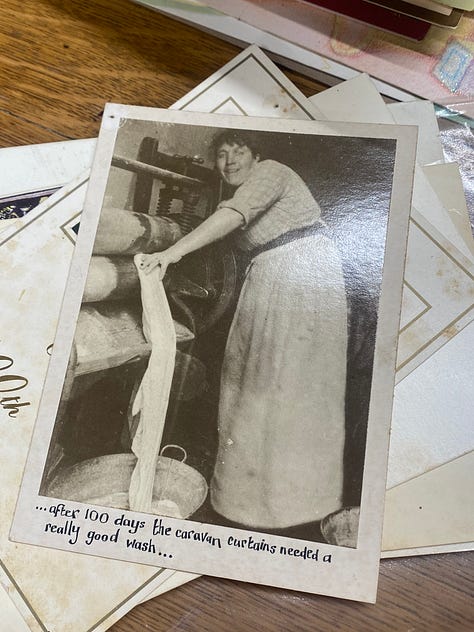

Some touched on wider political questions, or referred to adjacent industries, and some were specific to the WAPC movement, itself spread across the country. Of these, two favourites included one image of a woman with a mangle, glued onto some card, with a caption about the caravan curtains added in felt-tip below (a reference to the caravan pictured in the above collage, the central base for the women at the camp). The other came to Lancashire from the Sheffield branch of WAPC, who launched their own hot-air balloon in 1993. (There are some amazing images of Bernadette Lingard, Judith Woodall and Dot Rodgers taking defiantly to the sky in that balloon, and in fact I think there’s something brilliant in the very image of hot-air balloon as political action, equally whimsical and provincial, grand and domestic at the same time. The image of a hot-air balloon now always makes me think of the final scene of Shelagh Delaney’s 1968 Charlie Bubbles, where Albert Finney heads up up and away in a drifting, surreal send-up of so many of the social mobility narratives of the era.) All of which is really only to gesture at the richness and imagination of these cards, and the scope for a long-form analysis of them, asking how image inflects text, or thinking about the affective power of the coloured biro scrawl, or interrogating the place of the postcard in British political history more generally.

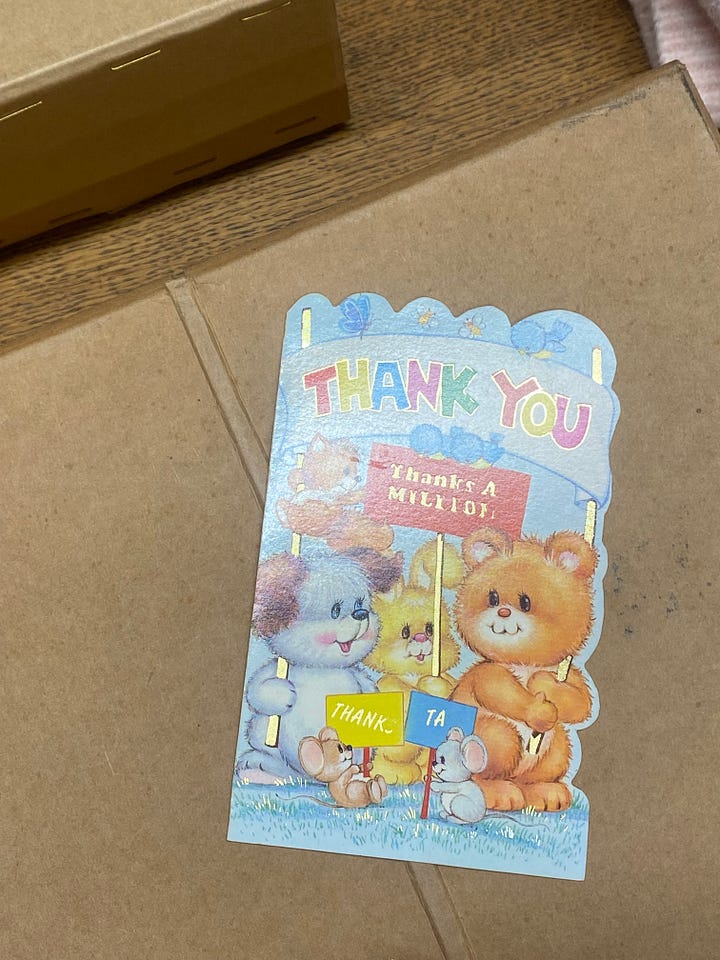

Yet what really matters is my feeling that such an analysis doesn’t only extend to those cards with an explicit official politics to them, but rather also to those you’d be less likely to find in a glass case, even in the most left-wing of museums. It was those cards, like the Valentines’ cards, from which the glitter came. They were not emblazoned with industrial satires or obvious solidarity slogans, and instead, they were often as intensely Clintons as could be. Sugar sweet bears holding placards to say THANKS A MILLION! / tiny golden labradors surrounded by festive baubles. Inside, messages in the very tone you’d expect: “thank for everything you’ve done for me - lots of hugs and kisses.” I suppose what I’m trying to do is to take the sugar sweet bears seriously as a mode of political articulation, and to try to urge towards a version of left-wing history that has some room for “lots of hugs and kisses.”

It’s perhaps only in placing those cards side by side along more traditional tokens of solidarity that the real effect can be gleamed, for what I’m urging is the fact that both modes must (and by neccesity long have) co-exist/ed. That which feels like it ought to be catalogued by the WCML, alongside that which seems in some way beyond the privilege of that categorisation - too pop, too kitsch, and let’s face it, too feminine. (I’m not trying to claim some kind of essentialist reading of Clintons, here, but rather to acknowledge the obvious fact that it is generally women who remember birthdays, women who send cards, women who are socialised to enjoy sugar sweet bears). What matters is that this box of greetings cards is intensely political in more ways than one. In forcing us to confront the aesthetic clashes (or at least, what we’re told are clashes) between strike banners and teddy bears, it forces us too to confront the same apparent clashes that have become so ingrained in our thinking about left-wing politics.

I was excited by the dust, but I was depressed by it, too. It exposed the very fact of the cards’ neglect. Why is it that those who have worked through this collection before me have seemingly not bothered to treat these objects quite so attentively as the rest? A similar frustration charges most of the work I’ve been trying to do over the past few months: part of what was so moving about going through this material was the sheer volume of communication, the outpouring of support, at odds with the narrative that words like “neglect” conjure up. Constantly writing about the historical neglect of working-class femininity in Britain can be a little depressing, and this huge mass of handwritten notes for the women at Parkside, pledging their support and solidarity and love and hugs and kisses, is a helpful reminder that the institutional ignorance I’m talking about is a question separate to that of the care and attention paid by those to whom these actions mattered the most. If anything, seeing that care and attention laid out in piles and piles of mass-produced glittery cards, was a useful reminder of why I think this work matters.

The glitter isn’t incidental. These details are testament to particular lives, lived in particular ways, more specifically, the lives of working-class women in the north-west in the 1990s, many finding themselves changed by the experience of political action. What I’m urging isn’t just the guilty, reparative inclusion of the gauchely girly, but rather the recognition that these aesthetics, these communicative modes, bring with them the particular subjectivities and experiences of whole swathes of individuals until now totally scratched out of histories of industry and deindustrialisation in Britain (even recent, apparently feminist ones) despite the fact that they were there, shaping history, Clintons’ bears and all. In many ways, this is what the project with NCME is all about – more on it soon. x