democracy at the deep end

deep dives, workers pools, helium balloon dreams

I had never thought that swimming was cool. It was the latex caps, probably, or the heady mix of chlorine and bacteria, or the simple fact of my very anxious childhood, and the intense fear of drowning that came with it. Swimming was icky floors with stray hairs, crap vending machines, and foam floatation devices with suspicious bites taken out. None of this much appealed, nor did I even have any sense that it might much appeal to others. As far as I was concerned, swimming was something that you might be forced to fake a sick note for, or at best, something you might do briefly on an annual holiday, with the keen promise of a pina colada at the end. Then, last year, I moved to London, and succumbed somewhat inevitably to the bourgeois lure of the lido. Guiltily pining for a Sweaty Betty swimming costume and keenly aware of the privilege of some mid-afternoon lengths, I wondered if it had always been thus, already knowing of course that it hadn’t. Despite the exclusivity that seems now to define them, these were, after all, intended to be public spaces. “Swim-for-All” as the Better chain (who now operate over 140 pools in the UK) call it, might at another time have meant something more substantial.

Charlton Lido, my walking distance pool of choice, was in 1939 the last municipal lido to be built in London. Its pleasingly modernist curves have now been somewhat obscured by Better branding, and journalist Vicky Frost recently noted that the pool “has the cool of neither Brockwell nor London Fields.” Frost might try telling that to the battalion of chic middle-class mums that descend daily from Charlton’s leafier surrounds, but her comment cuts at the currency of the lido within the strangely self-referential and faux-ironic gentrification culture now so common in London. This is the oddly apolitical realm of the Real Housewives of Clapton, which though funny, does perform an impressively apologist service for a whole generation of gentrifiers. Through RHOC, one can find both company and absolution: Forgive Me Father for I Have Purchased Perello Olives and am Pushing Up Rents. Or something to that ha-ha-ironically-posh-effect. This is a phenomenon that I regularly participate in, by the way, both the swimming and the ha-ha-ironic-posh culture beyond it. I can’t help but write how much I love that swimming pools are largely inhabited by older women, and the way that changes the atmosphere of a place. How I love the feeling of my body cutting through the cool water, how I love being good at something that terrified me for years, and the little rush of satisfaction that still comes every time.

All of which is incredibly boring to everybody other than the initiated and the damp. Everybody knows that affluent white women love swimming; we tell everybody, over and over. There’s been a great spate of writing on swimming over the past few years, and the vast majority of it authored by a very narrow subset of society. There are wider problems at play here, some of them explored in Frank Awuah’s Blacks Can’t Swim, as well as some basic exclusionary factors (at Charlton, for instance, it costs nearly thirteen pounds a swim). For whom is the lure of the lido a feasible one? More might be said about the specific characterisation of outdoor swimming, namely the embracing of elected physical hardship (see also: Barry’s Bootcamps, Tough Mudder, Wim Hof worship and a whole host of other masochistic pursuits) in a manner perplexing to those short on time, with no shortage of meaningful, non-simulated difficulties to overcome.

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of conserved or restored pools supported by organisations such as Future Lidos are found in the south of England. I spend a lot of time personally lamenting the loss of the Super Swimming Stadium in Morecambe, where I grew up.

Built in 1936, the Super Stadium was said to be the largest outdoor pool in Europe, with room enough for 1200 swimmers and an audience of 3000. It hosted the Miss Great Britain and Miss World competitions for many years (evidenced in some truly spectacular photoshoots that leave no doubt as to Morecambe’s late-mid-century glamour) before it was totally demolished in 1976. It was incredibly beautiful, and designed to compliment Oliver Hill’s still standing Midland Hotel. The 20th Century Society tell us that, when the Governor of the Bank of England opened the stadium, he did so with the following words:

“Bathing reduces rich and poor, high and low, to a common standard of enjoyment and health. When we get down to swimming, we get down to democracy.”

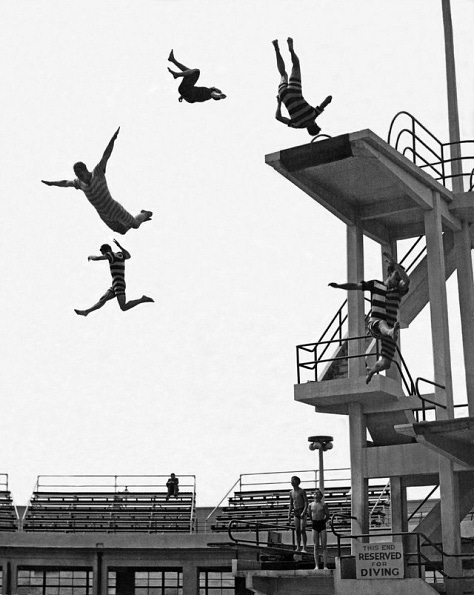

There’s something of a fiction present there, as there always is in rhetoric that revolves around great levellers, but the bold equation between swimming and democracy itself is one that I find it hard not to be provoked by. This month, I spent a week in Vienna, where I tried to swim almost every day. As I swam, I thought about that provocation, and in particular that former “common standard”: enjoyment. Questions of basic provisions, health, cleanliness, and attentiveness to the body, are all of course important – but what of swimming for pleasure? What of leisure as an end unto itself? There are photos of the Super Stadium in its heyday that I absolutely love, and that capture something of the potential meanings of public swimming, beyond the practical. There’s something in them of SuperMac, my favourite photo by Tish Murtha, in which the ordinary working person is seen to leap, boundless, through the air. In reality, these subjects are often being pulled, crashing down to the ground, and yet these photos allow them to soar. To embrace such images isn’t to deny the material circumstances at play, but to allow them to occupy, just for a moment, a space beyond. That same weightlessness might be read in the very act of swimming, as bodies force their way forwards through matter. Swimming isn’t the denial of resistance but a simulation of its temporary suspense, for a stroke, or a length, or an afternoon at the baths.

I vaguely knew of Red Vienna, the social democratic government that held power in the city between 1918 and 1934, before travelling to the city, but that knowledge didn’t extend much beyond a basic image of the Karl Marx-Hof. I certainly had no idea how expansive the Red Vienna program was, though there are good pieces in Jacobin and elsewhere if you’re keen to know more. Most surprising of all was just how important swimming was to the Red Vienna vision, which not only saw the building of over 64,000 homes, but 26 unique pools. Many of these remain publicly accessible and cheaply available in Vienna today. There are some great outdoor lidos, but the gem of what remains is the indoor Amalienbad, a rich art-deco space in the Favoriten district of the city, inhabited predominantly by the Vienna’s working-class. Karl Seitz, mayor of Vienna between 1923 and 1934, was reported to have said of Amalienbad’s opening: “air, light, and water – they're what the working person needs,” and yet the space is about so much more than the basic or elemental. These pools were obviously important for eminently practical reasons (not least providing many workers with their only access to washing facilities), and yet I don’t think it’s a retrospective romanticisation to think about them as complexly sensual facilities, too.

When the light pours in from the glass ceiling at Amalienbad, it bounces gently off the brown and gold surfaces that cover it, bathing the swimmer in a warm glow, the luxuriousness of which is difficult to ignore. After a swim, visitors can also spend time in one of several art-deco saunas that form part of the complex, and as with the vast majority of the Viennese pools we visited, there were an abundance of striped sun loungers, and a restaurant. Stray hairs and crap vending machines seem universes away. These are spaces designed for taking your time, stretching out over several hours, places that stress the rich plurality of LEISURE in the strongest possible terms. They are spaces built to give the gift of that leisure to the cities’ labourers above all. There is a strong tradition of this in Vienna, considered for instance in this Tribune piece on Alt-Erlaa and rooftop pools. Swimming in Vienna, so far as I could see, partly remains as it once was: not a special treat from the struggles of a laborious life, nor the exclusive domain of those whose lives distinctly lack struggles. It’s simply a part of living ordinarily and well, a way of integrating pleasure into the everyday. None of this is to say that a smattering of swimming pools provide the perfect solution to all social ills, but it is to say that something seemingly quite small, like swimming, wields real social force. The benefits it provides are blurred; practical, economic, bodily, yes, but also intangible and softer, pleasures, sensual satisfaction, the feeling of some freedom, in the water and in life. It’s taking joy in amidst ordinary working life, rather than aspiring to a temporary escape from it. It’s soaring through the air, in the knowledge there is something warm to catch you.

This intermingling between social politics and pleasure isn’t one we often associate with the UK, though there’s a history worth celebrating there, too, one there isn’t the space to get to here. This morning, my mum and I drove to the only lido within reasonable distance from my parents’ house, the Ingleton Swimming Pool, in North Yorkshire. It was built over the course of a year, largely by striking miners from the local colliery. Spectators were reminded at its opening in 1934 that “all the work has been done by volunteers; the money spent raised by donations and subscriptions. We have now completed that which we set out to achieve.” A gift from the community, to the community, made possible by the villages’ labourers, and for them to enjoy, too. Another take on such connections can be found in Topical Budget’s No Coal Wanted Here! (1921) which eschews documenting an ongoing industrial crisis in favour of footage of Chiswick women smoking joyfully by the side of the pool, swimming caps and all. It’s a strange evasion of labour history, maybe, and yet at the same time a reminder in its very title of the actual inseparability of labour and leisure, public and private.

Though the craze for pools in Britain was never bound up with industrial politics to quite the same extent as in Vienna, there have been periods of particularly intense interest in these questions of pleasure and the so-called everyman. After the first rush of swimming in the twentieth century there was a second, as 200 new pools were built in Britain between 1960 and 1970. It might seem something of a leap, but this wave belonged to the same moment of Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price’s Fun Palace, “an interactive and adaptable, educational and cultural complex” designed to be built in London. The Fun Palace was a place where:

“the British worker can realize his potential for self-expression by dancing, beating drums, Method-acting, tuning in on Hong Kong in closed-circuit television, action painting . . . “

utterly bonkers, maybe even condescendingly detached, but also a project with pleasure and experiment as central, a conception of workers’ rights that goes beyond basic conditions, to consider the fullness of life and all its possibilities. There were no pools included in the plans for the Fun Palace, and yet this later expansion of public swimming can be understood to stem from a similar impulse: not just pragmatic betterment, but freedom, creativity, splashing, stretching out.

Catherine Slessor has described the history of public swimming in the UK as a “social, communal, sensual” one, which in many ways seems to jar with most people’s experience of the public baths, but that relationship, between the social and the sensual, is one I think we’d all benefit from re-emphasising. Swimming is just one way of beginning to understand it. It’s one that might warrant more thought. The social, communal, sensual history of the swim might just overlap with an alternative story for working people. That story incorporates imagination, play, and dreams of diving into the deep end, as well as digging up the space for it to be built.