On Friday, I got a train to Limehouse. Then another, to Southend-on-Sea. Then another, one way down the world’s longest pier (a must for fans of seaside absurdism). Then three more to end – back to the city, across to West London, and eventually heading home South East. A day spent on public transport is a day spent in the company of strangers, thinking about the pleasures and inconveniences of existing alongside other people, how we share spaces and move through places together. Also: the decadent aesthetics of seat upholstery.

I was in Southend to see After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989-2024, a touring exhibition from Johny Pitts and Hayward Gallery. There are some great reviews of this show already out there from Owen Hatherley and Nathalie Olah – this isn’t really another. Suffice to say I’m a huge fan of Johny’s work, and the re-enchantment of working-class worlds that this exhibition enables. I loved seeing work by Joanne Coates and Kelly O’Brien in person for the first time, both capturing the eery glamours of working women full of dreams and resilience. Elaine Constantine’s portraits of Northern Soulers in glorious flight and a surreal sectarian landscape by Hannah Starkey were also favourites.

The works that stuck with me the most, though, perhaps because of my day staring out of train windows, were those by Tom Wood. The exhibition featured four of his photos, part of a longer series collected as Bus Odysseys in 2000. The series documents Wood’s bus journeys through Liverpool across a period of twenty years. For me, these photos captured much of what was at stake throughout the exhibition. Margaret Thatcher has often been quoted as repeating the idea that “anybody seen on a bus over the age of 30 has been a failure in life.” There’s a great essay on the importance of this quote to Zadie Smith’s NW, written by Lauren Elkin in 2015 (years before her adjacent No. 91/92: Notes on a Parisian Commute).

So yes, we might see the sweaty, enjoyably crowded and affordable bus, taking working people where they want to go, as an enemy of the neoliberal project. What happens to those people when you take away their buses, not to mention their jobs, libraries, homes, and the basis of their communal identities? When history has ended, and there’s no such thing as society? The exhibition was partly an attempt to answer those questions, with one response being: they just keep going. They dance, drink, work, fight, carving out their own ways of life, often totally separate to ideas that might be imposed on them from above. A breadth of experience is important, and is reflected in Wood’s images. Some are ghostly, some feel gritty, some are brimming with an ambiguous longing, some jubilant and surreal. It’s obviously maddening that this diversity still needs emphasising in relation to the materially disadvantaged, but it does all the same.

Because I’m spending so much time at the moment thinking about working-class femininity, I was predictably drawn to “Chester Bus Station,” dominated by a suitably scouse looking woman in a hot-pink, shoulder-padded blazer. Her bouffanted hair mirrors that of the woman in the erotic beauty billboard behind her, and her gaze is almost filmic: pointed, wistful, regretful. Then again, have we really got any idea what she’s thinking? The feminine aesthetic at play here is similar to that seen in other photos by Wood, but what sets the bus images apart is the reflective surfaces that often mediate them, reminding us of Wood’s distance, not to mention our own.

Windows make themselves known throughout the bus project photos, generating a sense that looking out is just as important as looking in. This is another important connection to the show as a whole, in its emphasis on community-driven cultural production, rather than the usual cut and dry class voyeurism. Also, “looking out” in the sense that working-class people make art about the big wide world, not just the experience of being working class. There’s a huge amount of distantly looking in on communities too, of course, but the series’ strength is that it allows for both, holding space for the clashing of multiple gazes. Most of the moments captured by Wood are fleeting, and the safety of the moving bus can sometimes feel like a shield from any accountability to subjects. At other times, though, a gaze is powerfully returned. In “Kirby” and “Virginia Road,” young women stare right through the window pane, right at us. These photos don’t allow us to just drive on, but freeze us in our peering. Why are we looking? How are we looking? At whom do we choose to look? It’s hard to walk around the rest of the exhibition without plexiglass and its evocation of positional ethics sticking in the mind.

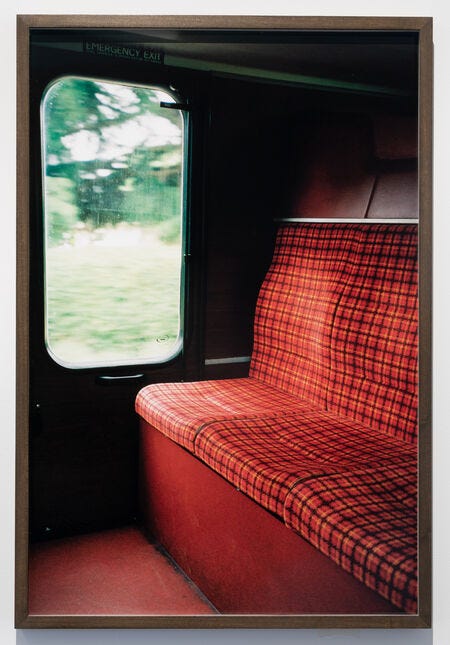

Then there’s the fact of making art, which we might too easily forget is what many of these photographers are setting out to do. Wood’s photos are spectacularly composed and highly curated. He’s making art on the bus. I can’t help but think of Mollie Balshaw’s work. Dripping chewing gum white against a recognisable blue and orange backdrop. MY STUDIO IS ON THE BUS. The pattern is not tonally dissimilar to that which dominates another photo from this exhibition, “The Delaine Bus, Peterborough.” Afterwards, that sends me down a rabbit hole: the uniformly dizzying spectrum of moquette. Which is, if you didn’t know, the name of the “strong, beautiful, easy-to-clean and durable” material almost always used to upholster the seats on public transport.

Moquette is, apparently, quite a British phenomenon. Why have wipe-down, plastic, nondescript seats when you might have strange, fuzzy fabrics, living room style? Some are migraine inducing, others spectacularly art-deco, but they all undeniably invite artistry into the communal journey. If the “sweaty, enjoyably crowded and affordable bus, taking working people where they want to go” really is an enemy of the neoliberal project, then what of these upholsteries, bringing a tiny, fizzing party to every seat? Moquette designs might have first been the domain of privileged designers, but now that the bus belongs to the low-paid, the inner-city-dwelling, the imagined failures, those patterns belong to them too. They’re designed to be durable and distracting, but they’re also bold and creative, an emblem of co-existence (like the nightclub sticky-carpets I wrote about last month). They’re flair both as a product of, and in the face of, the daily grind - something After the End of History seemed to me to revolve around.

The exhibition is in Southend until September, before a final stop in Nottingham until the end of the year. I came away from it thinking about windows, chairs, and working-class cultural production. Put otherwise: how people get to where they need to be, together, no matter how much people might try to stop them, and all the work that gets made along the way.