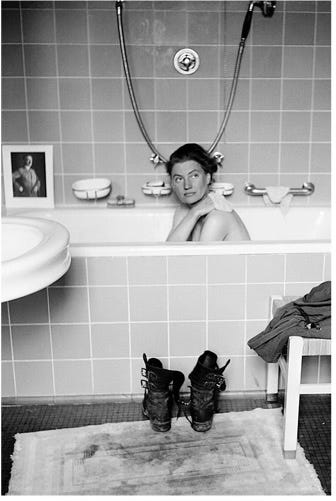

A beautiful woman is taking a soak in Hitler’s bathtub. There’s a framed portrait of the führer leant against the tiles. The woman is avoiding the gaze of the lens, performatively and prettily scrubbing her back, though the contact sheets show that this was just one of a few subtly different poses tried. There is dust from the woman’s combat boots, trodden into the bath mat, and a Life Magazine staffer, David E Scherman, behind the camera. Adolf Hitler himself has just committed suicide, 356 miles away, in Berlin. The woman in the bath probably does not know this yet.

“Why should I care about how it looked?”

In a scene from Lee, released last month, Lee Miller dismisses her son, questioning her on the optics of that photograph. That dismissal takes on something of an irony within the context of this film, one that I felt failed quite spectacularly to engage with the fascinating and often grim representative politics inherent to Miller’s photographs. Falling happily into the most obvious traps of the genre, it is oddly uninterested in the kinds of care that goes into how things look. A sexy photoshoot in Hitler’s bathtub is presented as mere pragmatic necessity. It is difficult to know where to begin.

Though it may choose to not much engage with them, Lee does nonetheless present a set of important questions, tethered to Miller’s complex life and legacy. At best, it presents us with an interesting series of events, about which we might go away and think, drawing our own conclusions. And it is undeniable that Miller’s life is one worth presenting. Born in 1907 in New York, Lee Miller began working as a model in her late teens. It is said that Condé Nast himself pulled her away from oncoming traffic, saving her life before immediately scouting her. In 1927 she made the cover of Vogue, a cityscape behind her, chic bob and angular face front and centre. After appearing as the model for a sanitary brand, she briefly fell out of favour, and instead travelled to Paris, where she rocked up at the door of the surrealist Man Ray, and demanded he become her mentor. These two points of origin: glamorous, implausible, and obviously made possible by a very specific set of social circumstances, capture something of the now heavily mythologised life of Miller. They also capture the dependence of that mythology on powerful men.

From here on in she would be, in the words of Angela Carter, “the universal muse of the surrealists,” the face (or, rather, the closed eyes, breasts, arch profile) of an age. Musedom, we all well know, is a thorny issue, yet it is incontrovertible that Miller did find herself surrounded – and for a time defined - by artistically revered men. Photos from the summer of 1937, in which Miller visited Picasso and Dora Maar in Mougins, epitomise the gendered aesthetics that often defined her. In one, Miller is joined by Ady Fidelin, Leonora Carrington and Nusch Éluard. The women lie, draped, docile, across one another, with expressions of either totally serene passivity or pure exhaustion. Each of these women were artists in their own right, yet the moniker of “Muse” plagued each of them, and that objectifying gaze was by no means only perpetuated by men. In another photo from the same summer, Miller photographs Carrington in a pair of small white pants, as Man Ray, at one time a partner to both, spreads his hands possessively across Carrington’s breasts. It is by no means remarkable to suggest now that surrealism itself was, no less than the world of commercial fashion through which Miller found her first home, a movement wracked by misogyny and violence, as well as being a movement that women actively shaped. Crucially, none of this is separable, as Miller’s own early photographic work shows. The surreal, the commercial, the conventional, and even the culinary, bleed into one another, resisting fixity. In biography alone, Lee Miller is an embodiment of a powerfully blurred sensibility.

As war broke out in Europe, this blurring of lines was to exacerbate. In December 1942, Miller gained accreditation as a US army reporter, taking up a previously unheard-of position, as official war photographer for Vogue Magazine. It is this period that Lee prioritises, and whilst an obvious commercial choice, this is one of its limitations. Miller’s life and career prior to her war work are only briefly alluded to: a woman holds a fish to her ear like a telephone, and Miller complains about Man Ray’s domineering nature. In one early scene, set during that aforementioned summer, Miller serves the group a meal. I peer at the screen, and am disappointed to see that it looks to be a rather austere salad, quite unlike the surrealist cuisine the artist would later be celebrated for, and had long had an interest in. It’s a minor detail, but reflective of the relative absence of Miller’s creative life from the film. This feels all the stranger, given it was only recently that Miller’s artistic output was given the attention it had long deserved. Anthony Penrose, Miller’s son, has himself written that many of her war photos reflect “the kind of image only a surrealist could take.” Odd, then, that Miller’s identity as such is nowhere to be seen.

And yet perhaps this very idea of demarked identity is exactly the problem. Model, surrealist, war photographer, archetypal bad mummy, frontline girlboss, cook, addict, artist, victim... Lee is certain of these alternative identity categories, to be included or omitted at its discretion, yet the film is not interested enough in the possibilities that might come from considering the connections and tensions between them. One thread that it does seem to posit, relating to Miller’s sexual trauma, is clumsily dealt with, and outdatedly evoked. Miller was raped and contracted gonorrhoea at the age of seven. As such, the film seems to suggest over and over, she has a particular insight into the violence of war. We might pause to wonder: what are the ethical ramifications of hammering home a connection such as this, positing the suffering of one individual in relation to genocide itself? This is simply how we make sense of tragedy; how we relate to others. But is it not also something of an appropriation, a robbing of the specificity of historic trauma? The enormity of this is more than Lee (nor I) can begin to take on, though an attempt, given the importance and indeed relevance of these contexts, might have been a start. In any case, the issue is less in the specificity of this connection – however speculative, intrusively presumptive, and historically/ethically questionable it might seem to the viewer, and more in the implicit suggestion that this was the only unique facet to Miller’s gaze. Her victimhood, it seems to imply, defined her work. We begin to wonder if the film was penned by an art-historian of the 1950s: never a good place to be.

In reality, it was partly penned by Miller’s own son, who’s 1985 The Lives of Lee Miller, Lee is based around. Penrose is, understandably, a fierce defender of his mother’s estate, but problems are bound to arise when one’s own son is the sole arbiter of one’s public legacy. Throw in some alcoholism, PTSD, and an openly difficult childhood, and these problems only intensify. There is no such thing as an objective portrait of a life, and Penrose’s own involvement in the film is meta-theatrically gestured to, close to its end, but this is itself a missed opportunity to delve a little more openly into the complications of familial legacy shaping.

Miller’s experiences as a woman are important to her story, a fact that has recently been hammered home again and again via a not so new, but newly shiny, reparative stand of feminist art history. Yet perhaps as a result of the trendiness of that topic, the film is in danger of oversimplifying Miller’s gendered struggles, and not engaging enough with the other immense privileges that made her story possible. The result is a Sheryl Sandberg, lean-in style characterisation of war correspondence, in which Miller ties her hair up to sneak into briefings, just won’t take no for an answer, and repeatedly seems determined to get to the front line almost exclusively on account of a bolshy ballsiness, rather than any humanitarian drive. Later on, the disappearance of Miller’s own friends is cited as an explanation, but the initial decision to go to war is disappointingly reduced by an emphasis on gender politics. If Miller is, in fact, there to prove herself as a woman: what next? What happens when that woman experiences warzones, enters Hitler’s apartment, or becomes one of the first reporters to enter the liberated Dachau camp? Luckily for them, the filmmakers do not have to answer this question unaided. Miller’s photographs are what happened - it is to them we should attend.

Yet despite the centrality of cinematographer Ellen Kudras as director, it is these photos themselves, or more specifically, the problems of politics and aesthetics that they produce, that are so lacking. Miller’s official capacity was as a correspondent for Vogue, and the film touches on the importance of this brief, in communicating global events to a demographic they would not otherwise reach. Yet this cannot be the end of that particular magazine’s relevance to the story being told. Becky E. Conekin has written that “as Miller has been posthumously recuperated as an artist, her relationship with Vogue and fashion photography have slipped from view.” Miller’s rehabilitation as Serious Feminist Artist has edged the fashion magazine, seemingly too frivolous, too commercial, out of its frame. This is problematic for multiple reasons, the most obvious being that it greatly limits our capacity to understand the aesthetic fullness of Miller’s images, and what made them unique. Lee shows us the moment in 1941 that her photograph “Women with Fire Masks” was taken, and in doing so cannot help but gesture towards the slippage between glamour, absurdism, and the blitz that image deals in. Yet then the film retreats. No further thought is given to those slippages, nor to how Miller’s medium and historical circumstance – rather than simply her personal traumas - might have shaped her work.

In 2003, Susan Sontag wrote Regarding the Pain of Others, a book length essay on representation, and war photography in particular. In it, she reminds us that “the photographic image, even to the extent that it is a trace (not a construction made out of disparate photographic traces), cannot be simply a transparency of something that happened. It is always the image that someone chose; to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude.” As we see a genocide now unfolfing daily via our mobile phones, the relevance of Sontag’s analysis has changed, but not faded. To photograph, even the most truly harrowing of scenes, is to frame, is to exclude, and to include, too. It is to make choices. It is to care about the way things look. How does one photograph a warzone, photograph Hitler’s apartment, photograph the liberated death camp, when on commission from Vogue? To ask such a question is not to suggest that Miller consciously took her subjects to be purely aesthetic ones, or to be any less important for being so, but to recognise that the political is, obviously, always aesthetic, and vice versa. It is to genuinely ask, whether that kind of background, that kind of brief, changes one’s approach to the photographing of history, consciously or not. In Miller’s case, though Lee doesn’t seem to keen to explicitly suggest as much, the answer is yes. Lee doesn’t want to suggest as much because the result is an uncomfortable collision, one that we find difficult to place. One that we should find difficult to place. The fashion photographer in the concentration camp is not an idea we enjoy. And so, the viewer is encouraged to feel that the fashion photographer Lee Miller has left the fashion back in London, and is a serious war photographer now. Aesthetics are not part of her remit. The commercial is not a concern. The film, as such, needn’t address either. Then, to the great imagined frustration of the film’s makers, Lee Miller climbs into Hitler’s bath tub.

Familiar with the photograph before seeing the film, I braced myself for something of a radical tonal shift as Miller and Scherman entered the apartment in Munich. How were we to get from this, quite sombre, quite uncertain, mode, to that image of the bath? But that shift never really comes, and the film is clearly keen to underplay the strangeness of the event. To note this isn’t to suggest that the moment might have been alternatively explained, after all, how could it be? – but instead to wonder if its radical, and upsetting ambiguities, might have been allowed to foster, to the ends of a more thought-provoking work, one that might do justice to Miller’s own. Instead, it retreats. Lee’s characterisation of this moment has been intensified by producer and star Kate Winslet, who, when asked in interviews about the photograph, has shrugged it off as one of pure pragmatism (unclean woman sees hot water), sporadically captured for posterity (she happens to have a camera...) “I think any woman can understand that” Winslet appeals. An echo of the words attributed to Miller, then. Why should I care about how it looks?

Because, as Sontag well accounted for, the totally unpragmatic, almost violently subjective dimensions of this photograph are what have etched it into history. Its power is partly in its pure shock value, the beautiful model in Hitler’s bath. There is the obvious glare of its sexuality, and its equally sexily inexplicable origins (how daring! How audacious in the face of all that had gone before). For some, its power lies in a narrowly conceived but coherent notion of ideological triumph, the beautiful American model in a defeated Hitler’s bath. Penrose suggests this image is best defined as one of “a victor.” Is it offensive? For some, unmistakably, yes. Miller remains incredibly privileged, and the incorporation of her naked body into the tableau feels a little off. Partly, because she is beautiful and perfectly posed, and because viewers don’t, traditionally, like beautiful models and politics to go together. Partly because Hitler’s portrait is watching her, claiming something of the image, sharing in our view. Partly because audacious frivolity is an unexpected response to genocide. But then, Miller knew all of this. In the posing, in the composition, in the inclusion of a framed photograph. Both here, and in shots taken in Eva Braun’s bed, her own sexuality was being wielded as a political tool. It was a means of personal rebellion, and of something much greater, a reminder now of what can and can’t be cleansed.

To position its viewers as this film does, watching Lee Miller somewhat naively snap a spur of the moment photograph, whilst innocently, practically, washing, is to fail to see that Miller saw us, looking at her. She knew what sold, what got printed, what looked good. She knew that politics, war, violence, were themselves highly aesthetic entities. She knew that the aesthetic was itself a weapon. She cared about how things looked! Lee erases much of this care, and it erases too, quite curiously, the very fact of David Scherman’s turn in the tub. For the majority of the film, he is a puppy-eyed, strait-laced accomplice to Miller, with little drive of his own. Yet Scherman himself was far more upfront about the politics of image making: “I was the pioneer of the faked, invented picture” he wrote, “during the war I shot nothing but.”It changes the image, and it strengthens the enormity of its politics, to know that Scherman, a Jewish man, got in the bath, and playfully posed too. Miller and Scherman had, just that morning, been among the first at the liberated Dachau camp. Over 30,000 people had been murdered there. Miller and Scherman “washed the dirt of Dachau off in his tub.” Lee gives a small moment, post-bathroom scene, to Scherman’s grappling with the enormity of what he has witnessed, not only as a journalist, but as a Jew. But both his Jewishness and his active and conscious participation in the bathtub photographs are, otherwise, erased. To acknowledge the photographs as a conscious and artistic attempt to process what was happening, for better or worse, is perhaps to admit their ambiguous, artistic, fuzzy, status, too much for the constraints of Lee. There, instead, photos are pure history. Miller is pure great woman. Scherman merely seems bemused, and the bathtub act is all hers. It is a strange aside, devoid of historical contextualisation, and with little legible connection to the rest of the film.

This compartmentalisation is the most significant reflection of Lee’s failures, both as a piece of historical testimony, and as itself a piece of art, unwilling to provoke or unsettle. So set is it upon stressing Miller’s importance, that it misses just why she is important. Not, surely, only for being a woman and being present, but for herself bearing witness in such specific ways, ways that make us tense, up to this day. Ways that make us uncomfortable, that recognise that Miller might have been flawed not only in her mothering style, but in the politics of her images, by no means unrelated to their form, their financial backer, their inherited style. We might disagree with those choices. With the ways in which Miller’s eye was trained to find beauty and neat composition, and still did so when faced with the most unimaginable horrors. We might disagree with her distinctly surreal renderings of the “absurdity” of war. We might disagree with Miller’s decision to climb into carriages full of murdered bodies, to photograph from the inside, to get up close. We might disagree, and still understand the importance of the very existence of these photos. Or we might not disagree at all. Yet to even have the option of dispute available, would perhaps stray too close to recognising Miller as a significant artist, and not, only, a recently excavated and glitzily female one.

It would come too close to recognising her war photos as aesthetic objects, a fate no image can be immune from, nor should be, if we are to read images critically. But then, at some distance from Lee, there is the woman who took a soak in Hitler’s bathtub for the readers of Vogue, who knew all that, of course. If nothing else, she cared about how things looked.